Geohealth

Exploring Well-being in the Netherlands

7 min

In this study, a group of ITC master's students explored well-being as a condition influenced by the spaces around us.

Our environments influence our emotions. The noises on our streets, the lush gardens and tranquil canals that we pass on our way. They all determine our ability to handle life’s daily pressures, work effectively, and contribute meaningfully to the community, all of which define mental well-being.

In recent years, growing awareness of mental health challenges has resulted in significant studies in this field. According to National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM), mental disorders alongside cardiovascular disease and cancer account for the highest disease burden in the Netherlands.

This guided our exploration into mental health not just as an individual concern, but as a condition influenced by the space around where you interact and live in.

Building on this momentum, we used the Global Challenges, Local Action GeoHealth project to explore how mental well-being might vary across spatial units and what roles our surroundings play in this, both physical/environmental and social.

The goal? To offer data-driven insights that can help communities and policymakers create environments that foster better mental well-being for all.

The literature review was conducted to understand the relationship between mental well-being and several socio-economic and environmental parameters.

After exploring various mental health parameters, the Mental Health Inventory 5 (MHI-5) describing the percentage of people having mental health complaints was selected as a dependent parameter, and the data was obtained from RIVM.

Potential factors contributing to mental well-being were identified, and several socio-economic and environmental parameters were chosen as independent parameters after considering the data availability. These include population density, education level, average income, general practitioners’ availability, crime rates, noise pollution (from car and train), blue spaces, and green spaces.

The data was then pre-processed to extract features of interest, remove missing values, and normalise the parameters. Spatial and statistical analyses were conducted using Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR). Finally, the interactive map and policy recommendation were formulated.

As previously mentioned, we conducted spatial and statistical analyses using GWR.

GWR is a spatially varying coefficient regression model. It was employed to explore the local spatial pattern between factors and MHI-5.

In the end, GWR yielded in a model from which the coefficients showed the correlation between each socioeconomic or environmental factor the mental well-being (reported MHI-5).

By applying GWR, we got the coefficients at the neighbourhood level for each factor. We further made boxplots of coefficients to show the distribution of the values of coefficients. Based on the map visualization and box plot of the results, we found the impact of the factors on mental health shows significant spatial heterogeneity in the Netherlands.

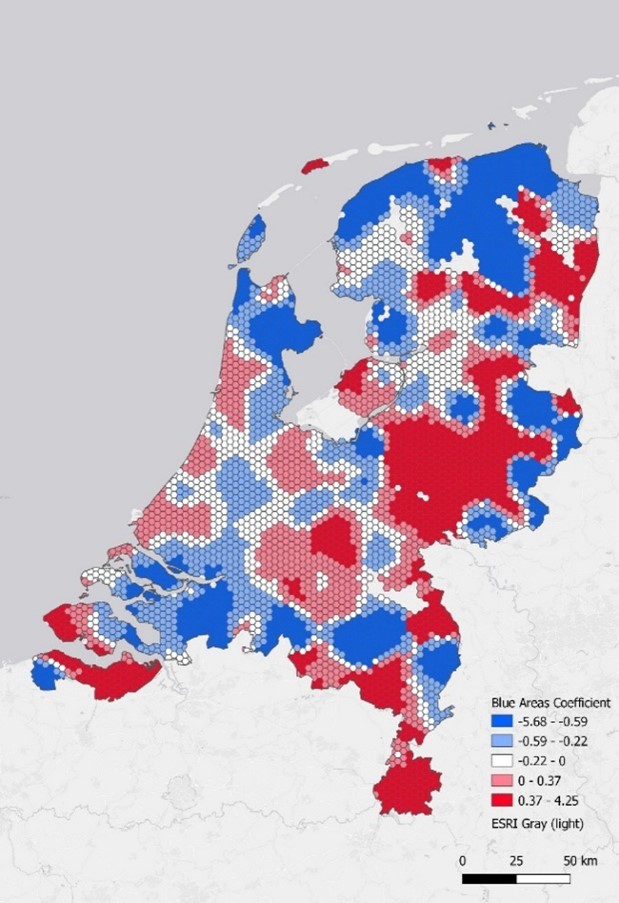

Spatial Distribution of Blue Space Coefficients in the Netherlands

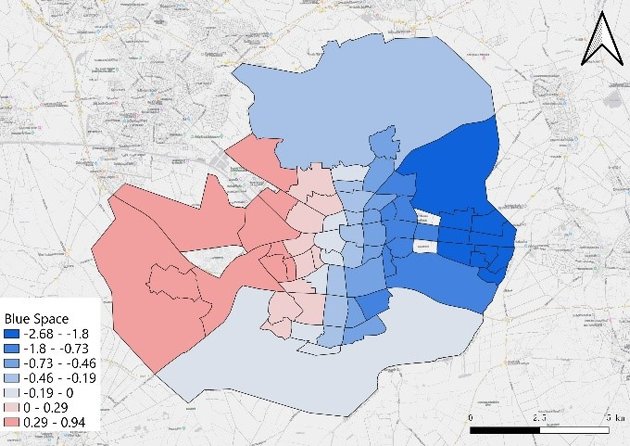

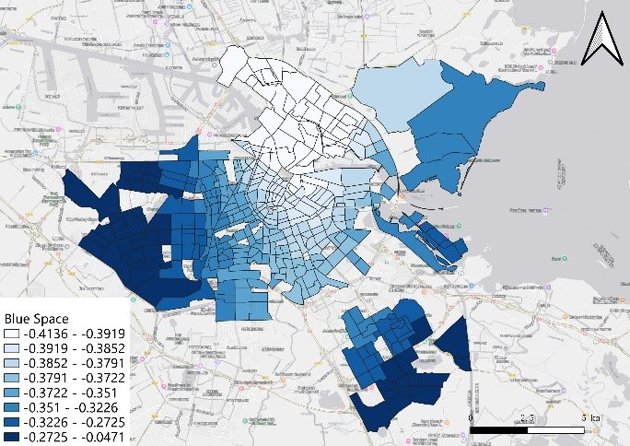

The following map shows spatial distribution of the coefficients of one of the factors, blue space. Considering the pattern of the same factor could vary in different spatial strata, we selected two municipality-level areas to interpret the results on a more local scale, which are Amsterdam and Enschede respectively. These results reflect the core idea we began with, where you live can shape how you feel.

In both cities, population density shows a significant positive impact on more mental health complaints. Income is another significant factor in the two cities, but it has a negative contribution in Enschede while it shows mostly positive value in Amsterdam.

For traffic noise, trains contribute to more complaints in both cities while car noise has only an observable impact in Amsterdam.

People with higher education levels tend to have worse mental health conditions based on the result but the correlation is not very significant.

In terms of green and blue spaces, blue space has a positive contribution to positive mental health in both cities and is more significant in Amsterdam. Green space shows positive coefficient values in both cities.

The number of GPs does not show a significant pattern in both cities.

Spatial Distribution of Blue Space Coefficients in Enschede (top) and Amsterdam (bottom)

We identified several key policy interventions. Some of the notable intervention suggestions comes in the arena of SDG 3 (Good Health & Well-being). We found that areas with the highest disparities were found in Groningen, Middelburg, and Leeuwarden.

At the planning level, provisions for adequate access to medical facilities should be ensured for vulnerable groups. Further navigating to bringing in more interventions, partnerships should be explored with private healthcare providers which could be tax breaks on medical resources, subsidized rent or negotiated access to government facilities and resources, to attract more providers to the underserved areas.

Before permanent facilities can be established, scheduled mobile health services could be introduced to temporarily bridge the gap.

In SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), promoting mental health literacy through the integration of school/workplace programs should be done, to help in early detection and timely intervention of mental health determinants. Training of volunteers/wellness “ambassadors” who can coordinate reporting, intervention, and detection.

Additionally, people feel safer when there’s a physical presence of security installations, creation of neighbourhood watches in collaboration with the police will deter crime. Joint response teams between police and community health workers to promote rapid response, especially at night.

Furthermore, in SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities), noise was identified as one of the key determinants of wellness. Some of the ways explored to address this included physical noise barriers where residential areas already exist near major transit routes, enforcing timing curfews for heavy rail and commercial vehicles near densely populated areas, schools, and other sensitive zones.

Enhanced open spaces were also highlighted as important, as it was noted that green and blue spaces must be accessible and inviting to have a meaningful impact on well-being.

This forms a starting point to understand how our surroundings relate to well-being. The local patterns we observed show that space indeed matters, but there's more to uncover. With room to grow and ideas to build on, this approach can develop into something that helps shape healthier, more supportive environments and, ultimately, lead to new ways of thinking about how we shape spaces that support how people feel and live.