Climate Change

Earth from Space: Smoke Plumes from Chile Wildfires

3 min

Researchers take a multidisciplinary approach to understanding the kinds of choices people make in the context of energy poverty.

The transition to a low-carbon planet is likely to cause rising energy costs. This could create a serious dilemma for citizens.

Should they spend more of their available budgets on energy, or prioritise other needs over comfort?

The world is gradually moving from fossil fuels to alternative energy sources. While this energy transition is a good thing in itself in terms of addressing climate change, there's also a risk involved.

Since the new energy systems may turn out to be more expensive than the traditional ones, citizens could experience a phenomenon that has been dubbed energy poverty (EP).

As a result, these people may be forced to choose between spending their money on either energy or food. In other words, heat or eat.

In a recent study, researchers looked at how exactly people can be at risk of EP – and how changes in their spending on food and energy relate to the "heat-or-eat dilemma".

Energy poverty has consequences for the quality of people's nutrition as well as their well-being and mental health.

Traditional methods of measuring EP tend to overlook such cross-sector issues.

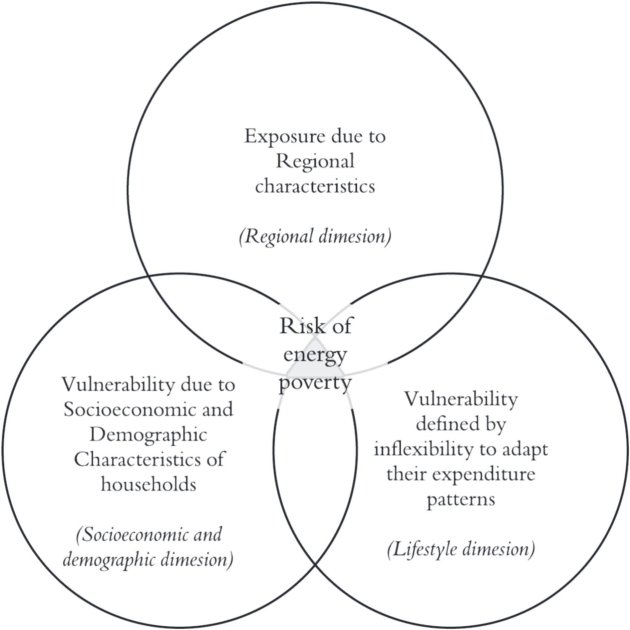

To address this, the study proposes a multidimensional approach. It looks at how regional, lifestyle, and socioeconomic and demographic factors influence the way households approach their energy and food needs.

Based on these three dimensions and using reliable open-source spatial and statistical data, the researchers created an index that maps which European regions are most at risk of EP.

This Heat-or-Eat Risk Index (HERI) is primarily aimed at helping policymakers to come up with more just and inclusive climate strategies.

The researchers define the regional dimension as the extent to which households in a certain geographic area are prone to food and energy challenges as a result of the energy transition (exposure).

The lifestyle dimension focuses on households' ability to adjust their spending habits to new conditions, and how their lifestyle choices influence their risk of EP (vulnerability by inadaptability).

And the socioeconomic and demographic dimension investigates how some groups of households – such as low-income, elderly, disabled, or people from a certain ethnic background – are more vulnerable to EP by definition (vulnerability due to socioeconomic/demographic factors).

In practice, the three dimensions interact to determine the probability of households suffering the heat-or-eat dilemma.

Framework depicting the risk of EP for households as a function of the three dimensions. Gorbig et al. (2025).

Having identified causes and indicators of EP through a literature review, and gathered relevant data from open sources such as Eurostat and the World Bank, the researchers got to work on creating the HERI.

In the regional dimension, their focus was on three key indicators: the extent to which energy is affordable for households, the degree of independence and resilience of energy systems, and the amount of stress households face when buying basic food.

For the lifestyle dimension, household budget data was used to analyse the balance between money spent on energy and food.

Finally, the socioeconomic and demographic dimension primarily looked at income differences per region. The resulting HERI was subdivided into five levels to present a clear image of regional EP risk.

The research shows that in the regional dimension, Balkan countries have weaker energy and food systems, while Scandinavian, Central, and northwestern Europe are more resilient. EP risk for southern European and Baltic regions is moderate.

In terms of lifestyle, households in southern Europe and the Balkan and Baltic regions spend more on food and energy, which makes them more vulnerable to EP. As for the socioeconomic and demographic dimension, southern Europe has the largest share of populations at risk of EP. Half of European countries have at least one household group in a critical EP position.

In conclusion, the authors surmise that the HERI is a useful platform for visualising how exposure and different types of vulnerability interact in the heat-or-eat space.

This underlines how important it is to take a multidisciplinary approach if we really want to understand EP risks.

In practical terms, the HERI provides a clear overview of the European regions where households are least able to deal with the consequences of the energy transition and associated socio-economic changes.

As such, it can help policymakers to understand why a region's citizens might be at risk of the heat-or-eat dilemma, and inform more just and equitable measures across Europe.

Moreover, the HERI's setup makes it transferable to other geographical contexts as well as to other essential domains such as housing, health, transport, and education.

This story is an adaptation of a journal article: Görbig, G. M., Flacke, J., Sliuzas, R., & Reckien, D. (2025). Unveiling energy poverty risk: A multidimensional analysis of the heat-or-eat dilemma. Energy Research & Social Science, 125, 104076.

It has been adapted with permission from the authors and in accordance with the copyright license CC BY 4.0

To read the original article, follow the link below: