Remote Sensing

What is Critical Remote Sensing and why do we need it?

8 min

Remote sensing is essential to Earth Observation, but it also has social and political implications. Critical Remote Sensing is a new perspective that can help to illuminate them.

The products of remote sensing, such as satellite imagery, are typically seen as neutral representations of their objects of view. However, remote sensing has political and social implications that merit further examination. Critical remote sensing (CRS) is a new perspective that sheds light on these implications.

For this story, we spoke to Associate Professor Mia Bennett from the Department of Geography at the University of Washington. Together with colleagues, Mia has been central to the establishment of CRS as its own subfield, and she's the lead instructor for the Critical Remote Sensing module, part of Geoversity's free Geotechnology Ethics course.

Remote sensing is growing in popularity, as demonstrated by the massive growth of objects launched into space in recent years, shown in the chart below.

With this popularity comes a growing faith from governments, companies and the general public in remote sensing.

Whereas before, as Mia observes, fuzzy black-and-white pictures of alleged weapons of mass destruction in the build-up to the Iraq war were treated with scepticism; now, "there's very little questioning of the data". Satellite imagery is frequently used by the media, often in place of more traditional - and impactful - pictures from war correspondents.

These images don't exist in a vacuum. "There's a whole political economy around the sale of satellite imagery that merits scrutiny", Mia says.

While the data has made real improvements in terms of its accuracy, "it’s still important to think about where and when the image is coming from, who captured it and why, how it was analysed or manipulated, and why it is circulating."

As well as the political interests underpinning the creation and use of satellite imagery, we must pay attention to how satellites see in accordance with how and by whom they've been engineered.

What a Chinese satellite sees in terms of 'features, scales and spectra', will be different from what a US satellite sees. They each bear a kind of subjectivity which, as Mia points out, "is scaled up when we use a specific set of satellite data to train computer vision models, or models which can detect, segment, and classify objects in an image."

Much like the issues we see with the large language models of generative AI, "they can only reflect the data on which they're built", says Mia.

As well as satellite imagery, AI and machine learning are being increasingly relied upon, not only for things like environmental management, but for social engineering, "say, predicting where and when protests might happen - that's when things get politically problematic."

"As Earth observation moves into the realm of Earth prediction", she says, "we need to tread carefully and critically – and that’s where CRS can hopefully prove useful."

Mia had been working with satellite imagery since her PhD. She found satellite imagery to be "an incredibly powerful and revealing type of data, but also one that has a lot of mystery bound up in the pixels."

Mia had been researching the Belt and Road Initiative in remote corners of Russia and China, and started to think about how she might pair this on-the-ground research with her remote sensing analysis, to learn "what the pixels do and do not reveal".

During her PhD, her advisor had suggested that she do something with nighttime lights data.

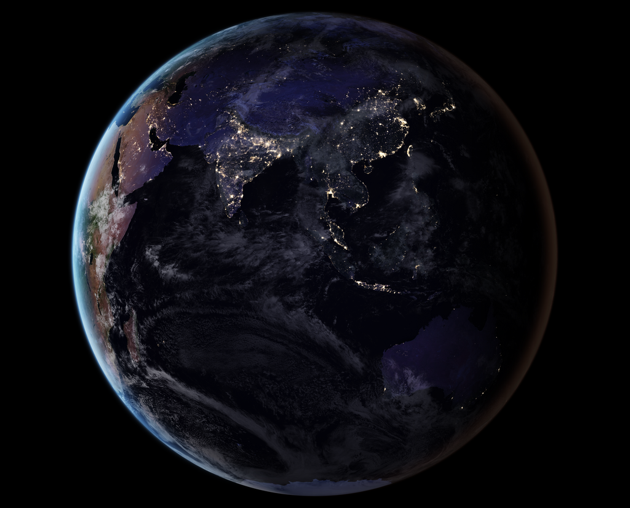

Looking at images of nightlights, it's tempting to assume that a high density of night lights correlates with a high degree of human activity. But, as Mia observed, this wasn't always the case.

Countries obsessively pursuing development, like China, for example, would have zones with a high density of lights, such as the Khorgos Special Economic Zone, but on the ground "not much is really going on".

Earth’s night lights as observed in 2016; they are drawn from a 2016 global composite map. NASA Earth Observatory, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Elsewhere, in the former Soviet Union, "there are countless settlements that are still brightly lit, but whose populations have cratered since 1991."

All of this paints a more complicated picture of nighttime lights than we would first assume: human activities don't always strictly correlate to trends in lights.

"This doesn’t mean that satellite imagery is inaccurate," Mia says, "but rather that it needs to be interpreted carefully. Illuminated pixels in one place don’t mean the same thing as illuminated pixels somewhere else."

She came to realise that, while Critical GIS was its own big subfield, there was no equivalent for remote sensing. Together with graduates from UCLA with whom she'd kept in touch - Colin Gleason and Luis Alvarez León, as well as Janice Kai Chen, graphics reporter at the Washington Post, she produced the scene-setting review paper called 'politics of pixels'.

Critical Remote Sensing is a module of the free GeoTechE: Geotechnology Ethics course, which explores the ethical and social dimensions of geodata technologies. The module was co-created between Mia and ITC, and she is the lead instructor.

In order for students to develop their data literacy, "it's important to know that even spaceborne data comes from somewhere", whether a company, a university or the military. As Mia says, "that provenance significantly shapes the data, who gets to use it, and how and when, too".

It's Mia's hope that by focusing on these issues, students can become more thoughtful remote sensing analysts. This is especially important as an increasing number of companies come to rely on satellite imagery. Employees will not only need to work with remotely sensed data, but "understand its implications for society and the environent at a range of scales, from the street to the planetary level".

Through a series of micro-lectures, Mia helps us explore the burgeoning field of CRS, taking learners on a tour through the political economy of satellites, the implications of the satellite gaze, satellite data production and consumption, and practises of CRS that seek to empower those traditionally on the margins of satellite data.

Follow this link to sign up to GeoTechE: Geotechnology Ethics.

And if you're curious to dive into the literature on Critical Remote Sensing, click here to read a journal article by Mia Bennett and colleagues, entitled "The politics of pixels: A review and agenda for critical remote sensing". And check out the paper Bringing satellites down to Earth: Six steps to more ethical remote sensing.

Login and start learning!