Land Administration Systems

Why managing land reform problems works better than trying to solve them

6 min

For much of humankind’s history, land has been an elementary resource to sustain human life. It brings together resources like water, plants, wildlife, and places to grow crops and build homes, and other infrastructure. Ownership of land or access to it have been common reasons for dispute, between people, between cities, between countries. Obviously, with a growing population, society started to understand it needed to organize land rights, setting the regulations and organizing the registration of land. Land administration became a societal institution that no single country could do without.

This article is about land registers and how they are or can be constructed. The GIP (Geoinformation processing) department of ITC, amongst others, develops methods of creating spatial information systems and land registers form an important, societally relevant category. Specifically, this article describes our effort to help bring a national land administration agency more solidly into the 21st century - which is after all the data and information century. We zoom in on one interesting challenge that can be seen as a problem of bringing to life - faithfully and digitally - land administration records that exist on an array of media from cloth to paper to foil to partially digital in a variety of file formats. Our scope of work in this project is wider, but here we look at this one challenge.

Our counterpart is the Guyana Lands and Surveys Commission (GLSC); it holds the mandate on registration of State lands in all of Guyana, on certified land surveying and on issuing land leases to individuals and companies, as well as collecting the fees for such leases. In that facility, it obviously maintains a land register: a repository of land surveys, issued land leases and a further number of land documentation products such as the registrations of administrative areas, Amerindian lands, mining and forest concessions and so forth. GLSC is the geospatial entity of Guyana, but it is not the only one.

GLSC became legally founded in its present form in 1999, but its predecessors were in place from the moment that Guyana accepted its State Lands Law in 1903, still then as a British colony. Consequently, the survey register dates back to at least those years, but older documents deeper into the 19th century are also held. They tell a rich story of lands in the territory, from colonial times to the present. Such documents are physical: written (later printed) on cloth, paper or foil, to this date the collection continues accumulating.

While physical documents are important to the extent that some countries’ laws demand that they exist and define ‘truth’, digital documents should at least co-exist with them in the digital age - if not become the more important central evidence of land administration.

The huge benefit that digital documents have over physical documents is of course that they can be made readily findable, analyzable and synchronously shareable. Once a transition to working fully digital has been made, documents cannot go missing so easily, paper stacks disappear from desks and land administration processes can be decently monitored. These are huge benefits in an era where the citizen has become more critical of government operations and wants to stay informed of “her/his file.”

This transition from a paper-based to a digital registration has presented register organizations the world over with substantial challenges. The maintenance of a vault with legal paper and cloth documents in a lowland tropical zone is already a challenge in itself (keep away the fungi); making the move to also hold digital copies adds massively to the problem space. For one, the operation of digital documents requires rather different staff skills and also attitudes, especially towards working procedures and monitoring these, towards data management and quality control.

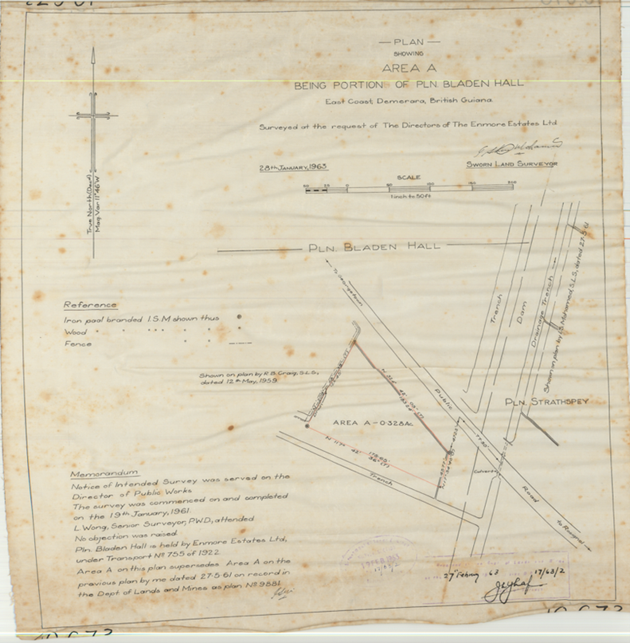

Figure 1 A survey plan from 1961 with a number of typical components: (a) title indicating geographic area, (b) map section that provides a sketch of spatial arrangement, (c) memorandum with information on survey execution, reason for survey and references to earlier relevant surveys, (d) legend or reference indicating symbology especially of survey monuments, (e) signature section. Survey plans hold numerical descriptions of land parcels, usually through side lengths and bearings, plus land parcel interspacings, which in Guyana are often called reserves.

So like other organizations, our client developed a digital vision to support its various business processes, amongst which is land lease issuance, with computerized information systems. Slowly it started to dawn that historic records of surveys and leases needed to become digital as well: these are the legal substrate upon which decisions to issue the next lease must be based. One shall not lease out some land that is already under lease, or that is not actually leasable because it is private property, within an issued concession, or under some other form of legitimate occupation.

Zooming further in, the challenge is best illustrated with a survey plan as certified surveyors have been producing routinely for decades under a strict set of requirements of survey operations and document content (see Figure 1).

In an original, paper-based workflow, say for lease issuance, staff would collect this survey if a lease is requested on or near to the land described, and cross-check for prohibitive spatial or temporal overlaps. With just a paper document, this could be only in one stack, meaning one lease application process, causing other such administrative processes to stall and requiring staff to implement an error-prone wait-for-document-availability queuing mechanism. So, with transfer into the digital age the challenge is how to extract from paper (or cloth) survey plans the information that is required for operational administrative purposes digitally. Such information is obviously both spatial (the map) and non-spatial (the title and memorandum at least). And we should point out here that the registry holds around 80,000 survey plans…

In this article we’ve given the context for the digitization of survey plans. If you’d like to know more, read the next article in the series which outlines a New solution for digitizing survey plans.